As an ecologist who teaches a wide array of biology and environmental science courses, I was intrigued by the announcement for “Jordan: Sustainability at the Margins,” an ACOR-CAORC faculty development seminar. CAORC’s summary about the importance of bringing a global perspective to the classroom resonated with me, the topic sounded like a good fit for my courses, and it was a region I had never visited before. I applied in hopes of enriching my courses with firsthand experience of a region shrouded in misunderstanding and conflict.

Although the seminar had a strong focus on sustainable tourism rather than ecology, I learned something of personal and professional interest at every stop along the way.

This was my first time visiting a country in a global development category different from that of the United States.* Time and discussions with ACOR staff and local guides were necessary to get a feel for how and why priorities can differ among nations with regards to ecological sustainability and sustainable tourism. When I see a site like ancient Petra or any of the other places we visited, my mind immediately goes to the ecological impact of having many tourists coming through the area, as well as what safeguards are in place to reduce impact on the environment.

SHORT VISITS, LONG-TERM EFFECTS

Preservation of archaeological sites in itself helps preserve the local ecosystems. Preventing development and restricting access to an area creates a safe space for local flora and fauna to flourish, such as has been discussed previously on the ACOR blog by former ACOR-CAORC fellow Omar Attum.1 However, opening sites to tourism can have an impact on the environment.

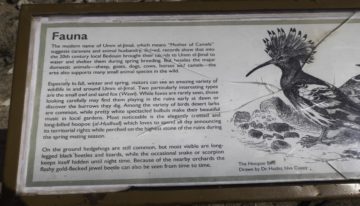

One way that archaeological sites help protect the environment is by educating visitors about the local ecosystems. For instance, at Umm al-Jimal there was a very well-done interpretive sign about the wildlife one could expect to find at the site. Interpretive signs that discuss the native wildlife help protect those very animals by making people aware of their existence and, by extension, of the importance of protecting the site not just for the rich heritage and history it conveys but also for the animals that call it home. Umm al-Jimal also boasted a beautiful garden of native plants at its entrance.

Bringing in visitors from abroad increases the chance of invasive weeds taking hold. Non-native plants can outcompete native plants, thus having an impact on organisms that rely on the native plants for food and shelter, which in turn disrupts food webs. Increased numbers of visitors can also lead to an increase in litter, particularly in areas lacking infrastructure for handling waste and recycling.

Every site we went to seemed to be used as grazing lands by local shepherds. Although domestic and wild animals can coexist, grazing livestock compete with native wild animals for food. Animals can also spread weed seeds. Livestock that are grazed at these sites can also damage exposed archaeological remains and infrastructure aimed at preserving sites and monuments.

DESERT ENVIRONMENTS

I have an affinity for desert landscapes, and thus our first views of Wadi Rum, with sharp peaks rising off the desert floor, tugged at my heartstrings. As we toured the area, the landscape only became more striking and impressive.

Ecologically, I had the hardest time with the vehicle tour we took in Wadi Rum. Deserts are some of the most fragile ecosystems, and the number of camps and the associated traffic needed to bring in guests and supplies surprised me. It was clear that there were certain routes the tours followed, but the tracks were spread out, increasing the area affected. Impacts of concern in areas like this include soil compaction, which reduces soil permeability to water (which can in turn limit plant growth), and vehicular pollution.

Although the vehicle tracks were distressing and seemed to cover a vast area of the desert, I had to remind myself of what our hosts Hattim al Zuwaidya, of the Wadi Rum Protected Area, and Tarek Abualhawa, heritage consultant with USAID SCHEP, told us about the area before our tour.

The area open to the camps and to tourism, as well as to film production, is just a small portion of what surrounds the heart of the Wadi Rum desert. The interior is protected, and there is an active research program, in concert with local universities, to study the desert and the biodiversity of the region. They also told us about recent efforts to reintroduce the oryx, which had been extirpated in the 1930s. Furthermore, the introductory tourist guide to the desert, available free of charge at the visitor center (see right), addresses the fragility of the desert, acknowledging that high tourist volumes have caused environmental problems. The guide describes a conservation program that is working to reverse those issues and to protect the desert from further harm. It outlines how visitors can help with protection efforts. Not everyone is lucky enough to be addressed by the director of the protection program, so it was wonderful to see that this information was included in the brochure for general visitors.

As I was assessing the potential ecological impacts of each site, I had to remind myself that the priority was to help the local communities while protecting archeological heritage. That, in turn, goes a long way toward protecting the natural lands around those areas. The ecological concerns I value in the U.S. context were not entirely off the radar in Jordan, only perhaps further down the priority list.

It didn’t escape my notice that, along the way, we passed many examples of ecologically sustainable practices and technology in active use. In particular, we saw such practices with respect to water, one of the scarcest natural resources in Jordan. Water management has been a key aspect of life in Jordan since antiquity. We saw the ancient cisterns at Umm al-Jimal and the lined and covered water channels carved along the length of the Siq in Petra to bring water into the heart of the old city. We saw how small community garden plots in Aqaba, as well as larger fields we passed along the Dead Sea Highway, were being irrigated in such a way as to bring water to only the parts of the fields that needed it. We learned about water management from IFPO researcher Myriam Ababsa in a discussion about the Amman Climate Plan and Sustainable Urban Expansion plan for Jordan.5 Water is even piped more than 300 km from Wadi Rum to Amman through the Disi pipeline, and is used to fill water tanks in the capital.

When you have a fixed amount of water to get you through the week until the next delivery, conserving that water comes much more naturally than it does when you can turn on a tap and know there is a virtually endless supply. Fellow seminar participant Joylin Namie of Truckee Community College in Reno, Nevada, further addressed sustainable tourism with respect to water in a recent article on the CAORC blog.6

We also saw ample evidence of ecological sustainability in the use of solar panels throughout the country. I particularly noted the solar panel and small windmill at our lunch spot in Wadi Rum, and those on the kiosks in Petra. We also learned that many families in Amman use solar panels to provide them with hot water.

On our trip from Petra to Wadi Rum, we passed a windfarm with windmills generating electricity on a large scale, as well as a billboard that advocated ecologically sound lifestyles (see the slideshow below).

The people and landscape of Jordan, the juxtaposition of the ancient with the modern, and the push for sustainability captivated me throughout this trip. I intend for my next visit to Jordan to take place in the springtime so I can capture with a camera some of the amazing wildlife that calls Jordan home and explore the ecological preserves that we did not have time to visit this time around.

Notes

*[The United Nations Human Development Index, a numerical indicator combining national income per capita, education, and health outcomes, classifies Jordan as “High Human Development.” Jordan is known regionally for high educational achievement and inbound medical tourism. Even though the World Bank classifies Jordan as “Upper-Middle Income,” the gross national income (GNI) per capita in Jordan in 2019 was only 6.5% that of the U.S. ($4,300 vs. $65,760). You can compare these and other figures at The World Bank “GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$)” page.—Ed.]

References

1 Attum, Omar. 2018. “The Biodiversity Value of Archaeological Sites.” ACOR, 2 August 2018. https://www.acorjordan.org/2018/08/02/omar-attum-acor-caorc-biodiversity-archaeology/, accessed 2 July 2020.

2 De Vries, Bert. 1995. “The Umm el-Jimal Project 1993 and 1994 Field Seasons.” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 39: 421-435. http://publication.doa.gov.jo/Publications/ViewChapterPublic/1040, accessed accessed 2 July 2020.

3 Nahhas, Roufan. 2019. “Jordan’s Umm el-Jimal: A Village Frozen in Time.” The Arab Weekly, 6 January 2019. https://thearabweekly.com/jordans-umm-el-jimal-village-frozen-time#:~:text=In%202016%2C%20919%20tourists%20visited,of%20Tourism%20and%20Antiquities%20said, accessed 2 July 2020.

4 Arraf, Jane. 2020. “‘1st Time to See It Like This’: Petra Tourism Workers Long for Visitors to Return.” NPR, Morning Edition, 6 May 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/06/850157824/1st-time-to-see-it-like-this-petra-tourism-workers-long-for-visitors-to-return, accessed 2 July 2020.

5 The World Bank Group. 2018. Urban Growth Model and Sustainable Urban Expansion for the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: Final Report. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/983981555961147523/Urban-Growth-Model-and-Sustainable-Urban-Expansion-for-the-Hashemite-Kingdom-of-Jordan, accessed 2 July 2020.

6 Namie, Joylin. 2020. “Lessons in Sustainable Tourism from Jordan.” Council of American Overseas Research Centers, Field Notes, 1 April 2020. https://www.caorc.org/post/lessons-in-sustainable-tourism-from-jordan, accessed 2 July 2020.

Marjolein Schat is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Thompkins Cortland Community College, NY, where she teaches biology and environmental science. Marjo has a PhD in ecology and environmental science from Montana State University, where she focused on invasive species management and plant-insect interactions in a biological weed control framework. Marjo also teaches science courses through the Cornell Prison Education Program and has taught an ecology and diversity course for a group of home-schooled high school students.

Weedy vegetation at Umm el Jimal; the route through the site was not a maintained trail, allowing visitors to wander off-site.

Interpretive sign at Umm el Jimal outlining the diversity of wildlife a visitor might expect to see.

Domestic goats being grazed among the ruins in Jerash.

View from the camp where we had lunch in Wadi Rum.

Close up of a particularly popular spot for Wadi Rum vehicle tours.

View from the Wadi Rum visitor center, where we were treated to tea and a presentation.

Tareq Abualhawa, heritage consultant with USAID SCHEP (right), and Hattim al Zuwaidya, of the Wadi Rum Protected Area (left), explain the challenges of natural heritage sites to our group. Photo courtesy of Jack Green

Jeep tracks in the Wadi Rum Desert.

Solar panels bringing power to the camp where we had lunch in the Wadi Rum desert, demonstrating that ecological sustainability was at the forefront.

Lined and partially covered channel in the Siq, which brought water into the heart of Petra.

Solar panels at the kiosk at the entrance to the Siq.

Solar array on the roof of the “Why Not Shop” in the center of Petra.

Wind farm between Petra and Wadi Rum.

Small plots in Aqaba irrigated in a way that only brought water to plots that needed it.

Green themed billboard at an overview of Petra