by Sarah Islam

(Photo by Sarah Islam.)

For Islamic intellectual and social historians, medieval manuscripts are indispensable primary sources for investigating what ideas and perspectives were being discussed in a given time period and region. Islamic manuscript repositories are often difficult to access and the manuscripts they contain even more difficult to read and assess, requiring the researcher to become a self-taught expert in codicology. Codicology concerns itself with the study of the materials, instruments, and stylistic norms involved in the production of codices (bound medieval manuscripts). Familiarizing oneself with the materials used in book production, handwriting styles of specific eras, and the tools used in manuscript illumination can not only help identify the date and region in which a manuscript was produced but also help discover who the author was or what role he may have played in a specific social context.

While I was at the American Center of Research as an ACOR-CAORC Postdoctoral Fellow in 2023, my primary focus was to complete my book on blasphemy (sabb al-rasūl) as a legal category in medieval Islamic history, a project that entails researching and reading dozens of Mamluk manuscripts. Many historians are surprised to learn that Amman is home to a significant Mamluk manuscript repository — the Center for Documents and Manuscripts (CDM) at the University of Jordan. Across the street from the American Center, the CDM collection contains more than 30,000 manuscripts from the Ottoman, Mamluk, and Fatimid eras.

The CDM has become an important but untapped regional center for primary sources in recent years. The institution has been collecting digitized copies of Mamluk archives and manuscripts from other repositories in the Middle East for more than three decades. With the onset of the Arab Spring and the Syrian civil war, most of Syria’s libraries are now either inaccessible or destroyed. The digitized copies at the CDM are what remain, especially with regard to manuscript collections in Damascus and Aleppo (Fig. 1).

Colleagues often ask me how does one distinguish Mamluk manuscripts from those of other periods, such as the Ottoman or Fatimid eras, and how does one determine its specific attributes, such as age, authorship, and scribal history? In a previous Insights essay, I addressed the material construction of codices in an Ottoman context and how historians examine physical aspects of codex construction in order to date its manuscript. I shall now address how historians use calligraphic script to estimate the age and geographic origins of a manuscript, with special attention to the Mamluk era.

Typologies of Arabic Calligraphy under the Mamluk Empire

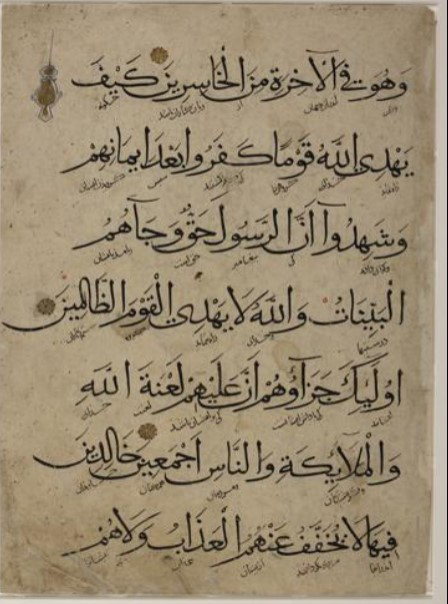

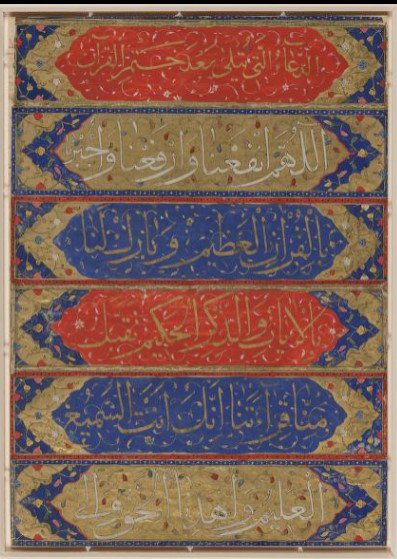

An important clue when attempting to identify the era and region in which a manuscript was produced is the style of handwriting or calligraphy used by the scribe or copyist and, in relevant instances, to what degree manuscript illumination influenced the lined text. Tenth-century Persian ‘Abbasid vizier Ibn Muqla (d. AD 940), who was both a high-level bureaucrat and famed calligrapher, played a significant role in canonizing and recording the history of the evolution of Arabic calligraphic styles (Safadi 1970: 17). We know from Ibn Muqla that, by the 10th century, six Arabic scripts had come to dominate Islamic calligraphy in the Muslim world: thuluth, naskh, muḥaqqaq, rayḥān, riqʿa, and tawqiʿ (Mansour 2011: 49–51). Yāqūt al-Mustaʿṣimī (d. AD 1298), the mamlūk of al-Mustaʿṣim, last ʿAbbasid caliph to rule from Baghdad, left his mark on script canonization as well by inventing new ways to cut reed writing instruments in such a way as to gain greater precision in strokes of the brush and pen. This increased precision allowed calligraphers to sharpen the ornamental distinctions between each style even more than was previously possible (Safadi 1970: 18) (Fig. 2).

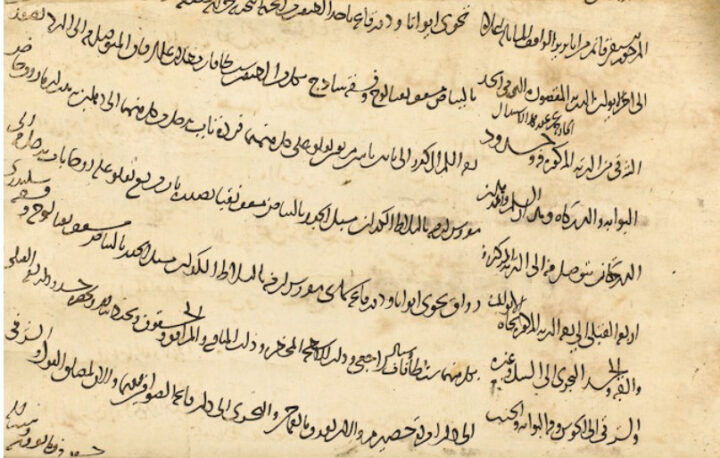

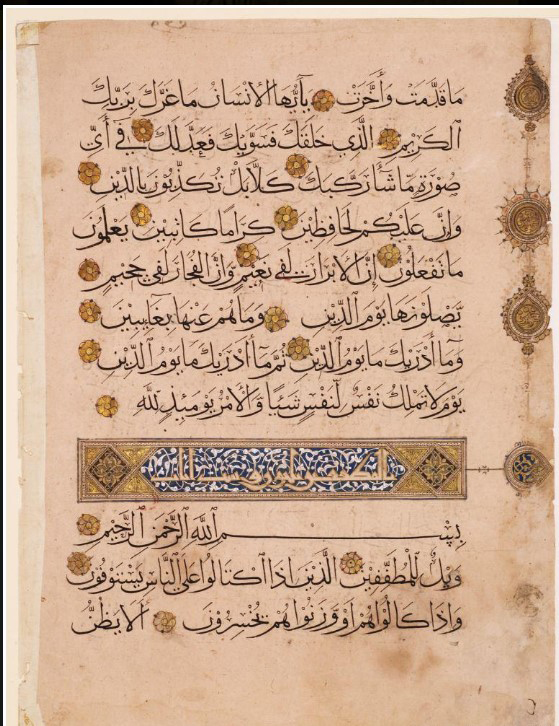

We know through 14th-century Mamluk-era Egyptian bureaucrat and scribe Al Qalqashandī (d. AD 1418) that the five scripts known to be in popular circulation during his time in the Mamluk Empire were thuluth, naskh, muḥaqqaq, riqʿa, and tawqiʿ. In other words, the rayḥān script, while still dominant in Central Asia, was no longer dominant in the Levant and Egypt (Blair 2011: 316–319). As part of their bureaucratic inclination for nomenclature and classification, late Mamluk-era scribes categorized scripts into two groups: rectilinear and curvilinear. Rectilinear scripts, which included naskh and muḥaqqaq, are straight scripts characterized by a certain vertical flatness (bast) and rigidity (yabs) of the sublinear brush strokes of Arabic letters. The sublinear brush strokes of Arabic letters in curvilinear scripts, which included thuluth, riqʿa, and tawqiʿ, on the other hand, have a rounded quality (taqwīr) (Blair 2011: 336) (Fig. 3).

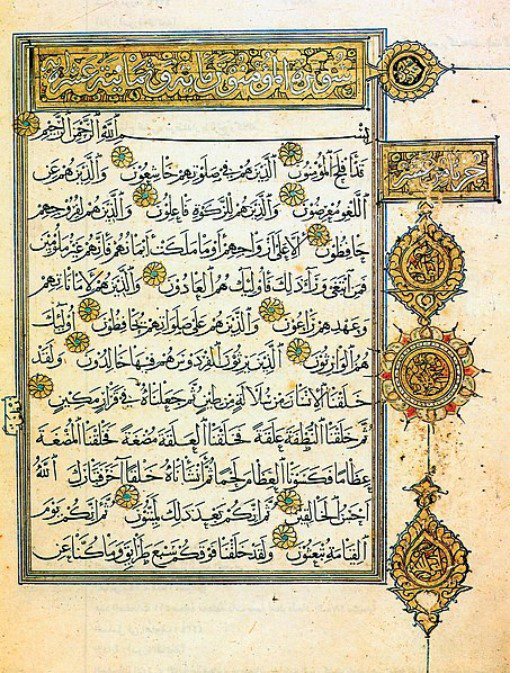

By the 15th century, rectilinear script was predominantly used by Mamluk calligraphers working on books that had a decorative component and were meant for public viewing, such as Qur’anic codices and other famous religious texts owned by the Mamluk Sultanate or wealthy patrons. Curvilinear script, on the other hand, came to be used largely by chancery employees, including state-appointed scribes and secretaries, for internal official documentation meant for record-keeping rather than decorative display (Blair 2011: 334–335) (Fig. 4).

Dating Mamluk Manuscripts Based on Calligraphic Style

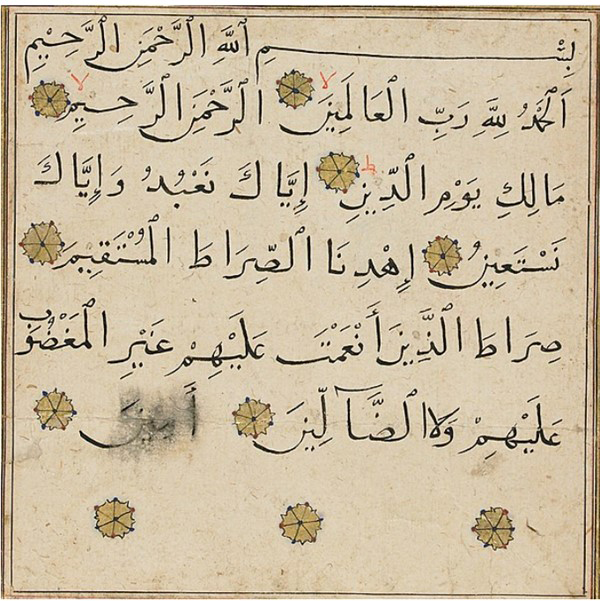

The usage of rectilinear scripts during the Mamluk era evolved over time, and it is in this context that knowledge of calligraphic styles becomes essential in dating manuscripts. The Bahri Mamluks, who were of Turkic origin, ruled the Mamluk empire from AD 1250 to 1382 and were succeeded by another Mamluk regime, the Burji Mamluks, who were of Circassian origin. The early Bahri Mamluks were far more interested in investing resources to maintain political stability, define territorial boundaries, and develop a far-reaching bureaucracy than investing in the arts. Codices intended for public display during this era up until the early 14th century were usually written in a conservative naskh script with far less manuscript illumination than what was found in the artistic productions of their eastern neighbors (Gacek 1989: 144) (Fig. 5).

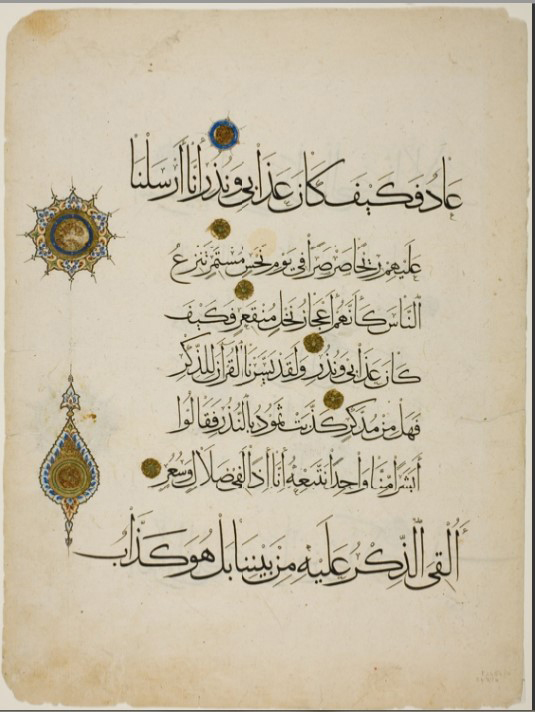

This status quo would change, however, and with increased political stability the Bahri Mamluks came to invest in a variety of artistic endeavors in the realms of metallurgy, textiles, and manuscript illumination (Mansour 2011: 31). By the middle of the 14th century, codices not only contained considerably more decorative illumination with increasingly expensive ink and materials but also shifted from being written in the simpler naskh script to the more decorative muḥaqqaq (Mansour 2011: 31) (Fig. 6). The muḥaqqaq script would continue to dominate until the 15th century. It would only be with the succession of the Burji Mamluks and subsequently the Ottomans that the naskh script would be reintroduced as the preferred calligraphic style once more (Gacek 2012: 140–141) (Fig. 7).

Differences in script usage and style were not only temporal but regional as well. Putting material differences such as ink and codex material construction aside, what constituted muḥaqqaq script in 14th-century Egyptian and Levantine Mamluk manuscripts had slightly different stylistic characteristics compared to muḥaqqaq in Persian manuscripts completed in Iran during the same era. For example, the alif in the Mamluk muḥaqqaq script measured ten dots in height, while the alif in the Persian muḥaqqaq script measured only eight dots in height (Gacek 2012: 140–141). Standard Mamluk manuscripts in muḥaqqaq script were eleven lines of text to a page, whereas those of the Persian Ilkhanate were five lines long, yielding much longer codices and more illumination per page around the text (Blair 2011: 321–322). Mamluk calligraphers, newer to the tradition of muḥaqqaq writing, struggled with consistent line and word spacing in ways that were noticeable compared to the precisely designed calligraphy and illumination completed by Persian Ilkhanate calligraphers (Blair 2011: 321–322) (Fig. 8).

Examining the sample of manuscript images just in this article, one could start to envision the sort of process a historian might go through to begin dating a manuscript. Taking note of the heavy and precise illumination, along with the curvilinear script, one might deduce the possibility that Figure 2 is an Iraqi ‘Abbasid manuscript. Comparing Figures 5 and 6, one might observe the sparse illumination in the former manuscript compared to the latter, as well as naskh versus muḥaqqaq script, to confirm that Figure 5 is from an early Bahri Mamluk era, and Figure 6 from the late Bahri Mamluk period, after the middle of the 14thcentury. The heavy illumination of Figure 7, coupled with its naskh script, could help identify this manuscript as Ottoman. And, finally, comparing the length of the alif in Figure 8 and Figure 6, plus noting the five-line structure and muḥaqqaq script, might help the researcher identify the former image as being that of a Persian manuscript and the latter that of a Bahri Mamluk one. Altogether, script identification and an awareness of illumination styles and varying types of codex construction are all elements that provide clues to the material historian on the date and regional origin of a medieval manuscript.

References

Blair, Sheila. 2011. Islamic Calligraphy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Foroqui, Suraiya. 1999. Approaching Ottoman History: An Introduction to the Sources. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gacek, Adam. 1989. “Arabic Scripts and their Characteristics as Seen Through the Eyes of Mamluk Authors.” Manuscripts of the Middle East 4: 144–149.

Gacek, Adam. 2012. Arabic Manuscripts: A Vademecum for Readers. Leiden: Brill.

Mansour, Nassar. 2011. Sacred Script: Muḥaqqaq in Early Islamic Calligraphy. London: Tauris.

Safadi, Yasin H. 1970. Islamic Calligraphy. Leiden: Brill.

Sarah Islam’s research focuses on the social and intellectual history of Islamic criminal law, and on how relations between Muslims, Jews, and Christians in the medieval context affected the development of jurisprudence and legal institutional norms across all three communities, despite internal polemics often arguing otherwise. Her first book project, Blasphemy (Sabb al-Rasūl) as a Legal Category in Early and Medieval Islamic History, examines the evolution of blasphemy as a legal category among capital crimes in Islamic legal history. Her research has been supported by the Charlotte Newcombe Foundation, Social Science Research Council, Fulbright Program, and the American Center of Research, where she has been an ACOR-CAORC Predoctoral Fellow (2015 – 2016) and ACOR-CAORC Postdoctoral Fellow (2022 – 2023). Her academic work has been published by Sage, Brill, and Oxford University Presses.