This written interview is part of a new series on Insights: “Ask A Scholar,” through which we highlight the personal experiences of fellows and other affiliated researchers. The following conversation with former fellow Waleed Hazbun (ACOR-United States Information Agency, 1997–1998), who is now professor of political science at the University of Alabama, took place by email in January 2021.

Thanks for joining us on Insights! Your scholarship has taken you to various countries and institutions around the world since the time of your residential fellowship at ACOR in the late ‘90s. Can you tell us a bit about the broad outlines of your career since then?

After my ACOR-supported fieldwork in Jordan on the politics of tourism development, I was able to return to Boston and finish up my PhD in political science at MIT. I was lucky and got an academic job at Johns Hopkins University teaching international political economy. With the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, however, I felt the need to focus more of my teaching and research on U.S. foreign policy and its impact on the Middle East. In Baltimore, I felt disconnected from the region, so in 2007 I took a leave of absence and served as a visiting professor at the American University of Beirut (AUB). I arrived in Beirut in the wake of the 2006 Israel-Lebanon war that devastated Lebanon. This experience reshaped my perspectives and interests while giving me new insights into the dynamics of regional geopolitics. I returned to the U.S., but two years later my department voted against allowing me to go up for tenure. Fortunately, AUB had an opening that year, and I was able to relocate to AUB in the fall of 2010. Again, I was very glad to secure a job, but more critically it was an amazing experience and opportunity.

I am so grateful that my career took this path back to the region and into an academic environment that supported interdisciplinary work and efforts to support scholarship focused on regional and Global South concerns rather than being constrained by U.S. academic hierarchies, concerns, and the increasingly narrow focus on quantitative methods. Soon the Arab uprisings broke out, and Lebanon faced its own internal conflicts and the spillover from the civil war in Syria. I learned a tremendous amount from students and colleagues, including Rami Khouri, whom I had met at ACOR in the late 1990s, and had the wonderful opportunity of serving as director of the Center for Arab and Middle East Studies (CAMES) and working with the Arab Council for the Social Sciences (ACSS), directed by former Yarmouk University anthropologist Seteney Shami.1

While I can honestly say I never imagined that I would end up living in the American South, in 2018 I took a position at the University of Alabama as part of an effort to help build a Middle East studies program. Beyond the opportunity to work with wonderful colleagues, I have been surprised by how interesting I find the experience, which has given me new perspectives from which to view U.S.-Middle East relations and ongoing changes in American politics while appreciating the great biodiversity and natural beauty of the state.

What topics and methodologies have occupied your work in recent years? How have they built on the research you were first engaged in while at ACOR?

It was while walking around Wadi Musa with ACOR fellow Najib Hourani that I formed ideas about the relationship between transnational flows and local territorial control that became the basis of the theorical approach presented in my dissertation, which compared the cases of Tunisia and Jordan, and I later developed in my book that the university press decided to title Beaches, Ruins, Resorts. I think the ability to easily travel across Jordan and explore its diverse archeological sites, rural landscapes, seacoasts, and budding ecotourism projects helped me to think in terms of geography and space and made seeing the contrast to spatial patterns of tourism development in Tunisia clear. Having drawn on theories of economic geography in my study of tourism and with the goal of seeing the dynamics of change in the Arab world as part of (rather than exceptions to) larger global processes (such as globalization), I approached the issues of international relations and U.S. foreign policy through the lens of geopolitics, that is, the territorial dimensions of international politics. My approach draws from the field of critical geopolitics and uses concepts such as “imagined geographies,” a concept developed by Edward Said and others that explores how space and territorial relations are understood through discourse, imagery, and other representations. Much of my work on tourism as well as international relations is concerned with rival ways regional and external actors “map” territories, flows, and the relationship between places.

From your vantage point as a comparative political scientist, how has the subject of your 2008 book (Beaches, Ruins, Resorts: The Politics of Tourism in the Arab World) grown and developed in the past twelve years?

That book was one of the first to address the political economy of tourism in the Arab world in a comparative manner. Meanwhile, geographers at the Center for Research on the Arab World (at University of Mainz in Germany) also produced a series of important studies. Today, there are far more scholars working on tourism (and related topics) in the Middle East from a range of disciplinary approaches. There is even a handbook of tourism in the Middle East and North Africa, and in my experience Middle East studies are pretty quick to recognize the importance of tourism in the region, including both its negative and positive impacts. Nevertheless, it is possible that the topic is still not taken seriously in many academic disciplines or faces the challenge of disciplinary silos, as tourism remains a topic best served by a multidisciplinary approach.

If you look at the numbers, internationally the tourism sector is currently in a crisis far deeper than at any time since the end of the Second World War. There are a lot of questions about which sectors and locations are going to recover. This crisis came after a decade during which tourism sectors in many locations across the Middle East and North Africa were hit hard by wars, political violence, and economic crisis. Tourism remains an important sector, especially in the Gulf states, with many governments continuing to stake hopes in using tourism as an engine of economic development. It is a cycle I have seen play out many times across the region. The recent moves towards normalization between Israel and the Gulf States and Morocco echo much of the discourse found in the 1990s during the peace process.

One of the most critical aspects of change in patterns of tourism development, I think, is the extension of some trends first recognized by the Mainz geographers (including Ala Al-Hamarneh and Christian Steiner). They noted how, in the years following 9/11, many Arabs redirected their tourist travel away from Europe to other parts of the Arab world. At the same time, domestic tourism flows and regional investment in the sector became increasingly important features. While these flows had always been there, with the volatility of western flows, governments and entrepreneurs came to give them more attention. While the vast wealth of the Gulf states is a critical driver in this process, more broadly the geographies of tourism are no longer mostly defined by western tourists, but rather by regional Arab tourists, religious pilgrims and Islamic tourism development, and the growing trend of halal leisure tourism. At the same time, tourism economies in many places, including Jordan, have become more highly diversified, including ecotourism, medical tourism, movie-based tourism, conference and meeting tourism, and sporting events, as well as heritage and cultural tourism, and are driven by new projects such as larger professional museums and cultural centers. Many of these trends are enhanced by the internet, social media, Airbnb, and the like, as well as the expansion of regional aviation networks, including low-cost airlines.

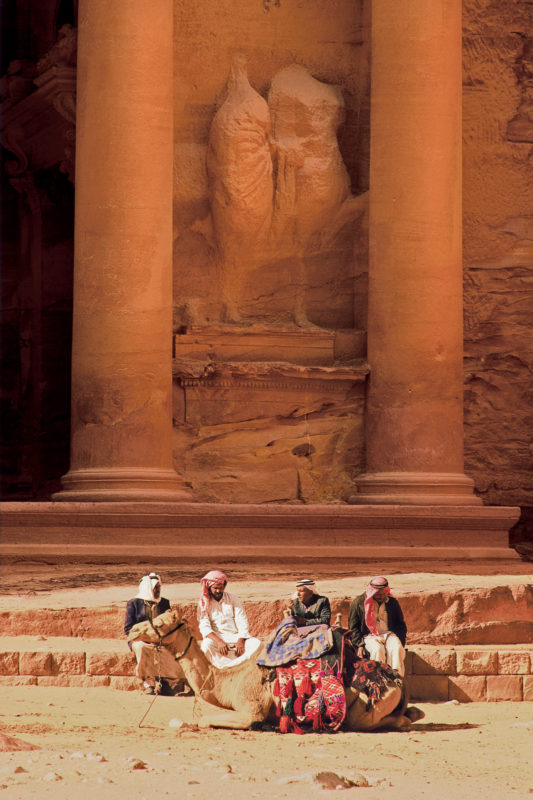

But I suppose that, for me as a scholar, one of the most rewarding trends to observe is the growth of local expertise in the field of tourism studies. In my interviews in the 1990s, I heard many complaints about outside tourism experts and externally developed tourism plans. In 2009, I gave a keynote address at a tourism conference held in Amman. There I met many young Arab tourism scholars and students. I was excited to find the Jordanians working on research topics such as the local views on the impact of tourism or different ways to promote tourism that appreciated aspects of the Jordanian landscape and ecology. In the years since, I noticed Jordanians such as Suleiman A. D. Farajat, who earned a PhD in tourism studies, has taught at the University of Jordan, and now serves as the chief commissioner at the Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority. Increased local expertise and professionalism is key to the future of tourism development in the region.

Do you have any advice for Insights readers who would like to get to know Jordan and the region better, especially from a comparative politics standpoint? Books or authors you would suggest, or online publications?

As I shifted to a focus on U.S. foreign policy and a concern for geopolitical developments at the regional level, I have not been able to follow Jordan as closely as I once did. In term of the politics of Jordan, I turn to the scholarship (and tweets) of specialists such as Curtis Ryan and Pete Moore. In terms of urban development in Amman, I follow the work of former ACOR fellow Najib Hourani. More broadly, I recommend both the current work as well as the very impressive publications archive of the Middle East Research and Information Project (Middle East Report).

In any case, for those outside the outside the region, an important tool to better understand Jordan and the region is to study Arabic and follow local events and media. One can also follow the English-language news sources from the region or ones with extensive reporting resources in the region, including outlets such as Al Jazeera and Al-Monitor. One can also now watch talks and other events taking place at institutions in the region, such as AUB or the ACSS, via their YouTube channels or livestreamed events. Still, there is no substitute for visiting and, more critically, living in the region for extended periods of time. One should travel extensively to see many places and peoples, but also live in places for long enough that they become familiar “homes” that you miss when you move away.

Waleed Hazbun is Richard L. Chambers Professor of Middle Eastern Studies in the Department of Political Science at the University of Alabama, where he teaches international relations and U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East and, when lucky, is able to offer a seminar on the politics of travel and tourism. He previously taught at the American University of Beirut and served as director of the Center for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies (CAMES). While its cover depicts Palmyra, his book Beaches, Ruins, Resorts: The Politics of Tourism in the Arab World (Minnesota University Press, 2008) was based in part on dissertation fieldwork in Jordan. He is a longtime reader and now member of the editorial committee of the Middle East Report and, since relocating to Alabama, serves on the executive board of the Southeast Regional Middle East and Islamic Studies Society (SERMEISS). He has two ongoing research projects. One addresses the politics of insecurity in the Arab World, and the other explores the global politics of airports, aviation, and air travel in the Middle East.

1. Editor’s Note: Seteney Shami is a member of ACOR’s board of trustees since 2012. Her most recent edited volumes, Seeing the World: How US Universities Make Knowledge in a Global Era (Princeton University Press, 2018) and Middle East Studies for the New Millennium: Infrastructures of Knowledge (NYU Press, 2016) are available to read at our library in Amman. Back to main article.

ACOR provides critical services to researchers around the world. As a non-profit organization, we can only do this thanks to your support. Click here to learn more about making a donation.

If you liked the above article, we think you may also enjoy this recent podcast interview (40 minutes), which published by our colleagues at the Richardson Institute in summer 2020: