by Osama Samawi

During my time as an undergraduate, I enrolled in a course called “Technology in Prehistoric Periods.” At 19, the word “technology” still made me think of computers, but I signed up out of curiosity. Prof. Maysoon Al-Nahar introduced us to the fascinating world of stone tool technology using Neolithic assemblages from Tell Abu Suwwan (ASW) (Fig. 1). That course gave me my first encounter with a real prehistoric stone tool—a moment I still remember vividly.

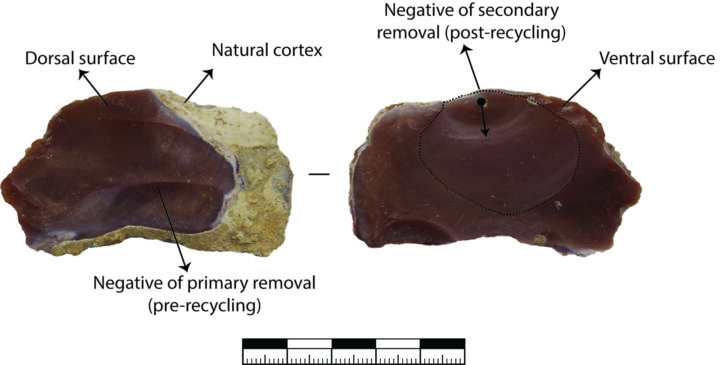

Years later, after I completed my master’s research, which focused on the African Middle Stone Age (c. 300,000–30,000 years ago), Prof. Al-Nahar invited me back to the University of Jordan to assist with her ongoing analysis of ASW (Fig. 2). Alongside other students, I helped sort and study thousands of stone artifacts. Among them, one type of flake caught my attention: It showed removals from its ventral surface, a practice not common at most prehistoric sites. These “cores-on-flakes” (COFs) were flakes originally removed from a core for everyday use—but here they were reused as cores themselves, creating more flakes (Fig. 3). It reminded me of repurposing a cookie tin to store needles and thread—but happening thousands of years ago. I decided to investigate this phenomenon further. I applied to the American Center of Research for funding in 2023 and was initially rejected, but I successfully received support in 2025 for my project “Stone Tool Optimization and Recycling Mechanisms in Tell Abu Suwwan (STORM).”

For the STORM project I examined 500 artifacts and worked in collaboration with Ruaa Al-Athamneh, a master of arts student, resulting in a combined dataset of 1,232 artifacts. Research took place at the University of Jordan, using both technological and typological approaches. Our main question was whether these cores-on-flakes represent deliberate recycling or a standard reduction strategy at ASW—a site located just meters from abundant raw material. Based on previous studies, one might not expect recycling at a site with such readily available stone, which made the investigation particularly intriguing.

Our analysis revealed that COFs were mostly created from reduction “waste” rather than formal cores. Size did not matter much. These flakes were selected to produce small, functional flakes—rarely more than two removals per flake. The resulting flakes were tiny, often less than 2 cm long, with minimal shaping or preparation. It seems the people at ASW were focused on quickly producing small cutting tools from existing materials rather than investing much time and effort.

The results show early humans deliberately recycling their stone tools. Even in a landscape where raw material was abundant, the knappers at ASW found ways to make the most of what they already had. Rather than creating a wasteful surplus, they turned old flakes into new tools—demonstrating ingenuity, adaptability, and resourcefulness. In other words, the COFs reflect a deliberate, flexible strategy for meeting everyday needs.

The outcomes of the STORM project are being prepared for submission to a peer-reviewed journal. Finally, I would like to sincerely thank the American Center of Research for funding this project, which made it possible to carry out the research and investigate these aspects of Neolithic life at Tell Abu Suwwan.

Osama Samawi is the 2025–2026 S. Thomas Parker Memorial Fund Fellow. He is a PhD candidate in the Interdisciplinary Center for Archaeology and the Evolution of Human Behavior (ICArEHB) at the University of Algarve, Portugal, where he researches the Middle and Later Stone Age in Mozambique. His work focuses on experimental knapping, lithic techno-economics, and the human-environment nexus during the Middle Stone Age. He is also engaged in research projects on the Middle Stone Age in Jordan, South Africa, and Oman.